|

It’s all in the idea: Student self-perception and musical success

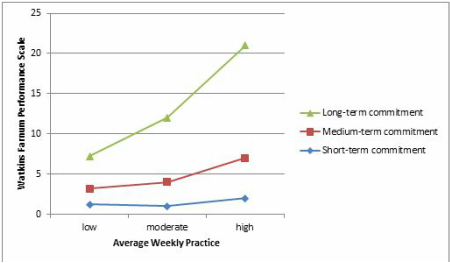

In 1997, a group of children (seven or eight years old) was studied from the time they choose their instrument to their graduation in high school. The researcher wanted to know what factors predicted their musical success or failure. Was it a sense of rhythm? More aural sensitivity or motor control? Their family’s income level? or their IQ? None of these factors were predicting the musical skill level of a student. Instead, it was their answer to a question that was asked before they had even started their first lesson: “How long do you think you’ll play your new instrument?” Those who answered longer periods were labelled “long-term commitment” in the top graph.1 When predicting musical performance level, the children’s initial commitment and their self-perceptions seem to matter more than their amount of weekly practice. This fact can be seen in the study’s graph at the top. For students who practice a lot, those without much commitment or self-perception as a musician will ultimately end up with a lower level than those who committed from the beginning and could envisioned himself or herself as a potential musician.2 Perhaps a teacher needs to nurture this vision of an ideal future musician as much as teaching motor skills, aural skills and intellectual skills. How does a teacher nurture the visions or self-perceptions of these potential musicians? One way to ignite that fire within is to expose them to a role model. In the field of sports, films and business, the media exposes all of us to role models to inspire us to reach for the stars. Unfortunately in the musical field, those role models are not as readily available. Whenever possible, be a role model, play for your student. Encourage them to go to live concerts, master classes, or to listen to more advanced students. Another way to nurture the vision of a future musician is to teach them with love. In the 1980s Dr. Benjamin Bloom surveyed one hundred and twenty world class pianists, swimmers, mathematicians, neurologists, sculptors and tennis champions. The majority of these experts rated their first teachers as “average.” These virtuoso pianists stayed with their first teacher for five or six years. The majority of the descriptions they gave for their first piano teachers were about how kind, nice, likable and patient their first teachers were. “The effect of this first phase of learning seemed to be to get the learner involved, captivated, hooked, and to get the learner to need and want more information and expertise.”3 Another facet of this nurturing process involves guiding students positively through unsuccessful attempts. “Great teachers see and recognize the inarticulate stumbling, fumbling effort of the student who’s reaching toward mastery, and then connect them with a targeted message.”4 A fear of failure can make students avoid experimentation and risk taking. Yet failure is at the core of the scientific method: without failed experiments one can’t eliminate hypothesis in the search for truth. Likewise, in music, mistakes are necessary for self-discovery, skill mastery, and good performance under pressure. Some teachers never force a timid student to play in front of others. Yet all failures can be turned into opportunities for learning. If a student believes that errors are just part of the learning process, he or she will recover from a performance with mistakes. Some teachers believe that they should write out all fingering for students. These teachers may believe that if learners make errors, the errors will be reinforced. In music learning this is especially true because “muscle memory” makes changing fingering hard once fingering is learned. In order to avoid “wrong” muscle memory when tackling a technically more challenging piece, teachers should spend time letting students choose fingering and then immediately give feedback. For intermediate students, a teacher can explain the phrases requiring lifts, range of keys within a phrase, black keys versus white ones, or structure of hand and fingers. For more advanced students, a teacher can explain why certain fingering works best for their particular physical attribute and what works best for that particular piece. Other topics related to fingering choices include what sound quality one aims for, which tempo, dynamic or articulation one wants, whether the reflexes or weight of our wrist, forearm or whole arm should be considered, or whether the previous and following beats or measures should be considered. I had the grace to have met a teacher who exclaimed, every time I made an unexpected mistake: “Wonderful! You’ve just stumbled where you normally do not. Let’s figure out what happened so you will secure it for future performances. Now where was it exactly?” Finding the location was a puzzle to be solved, after which we figured out “together” what was in the previous beat or motion, and what type of sound I should aim for. I was lucky enough to be taught by a teacher who believed that everyone can learn music, and who let me stumble, even in public. I learned how to pick up the pieces and continue, during a performance as well as after one. When making a mistake becomes an opportunity for learning, a student will tend to persist.5 Research suggests that kids who are praised for their efforts will more likely take on more challenges than those who are praised for their innate talent, or their successful results. It is all in the idea of learning: an error is not a measure of ability, effort changes the brain,6 and anyone can become a musician. A child has the opportunity to believe that he or she can be a musician. Our job as teachers is to nurture that vision by providing a positive nurturing environment. Notes: 1. “Commitment and Practice: Key Ingredients for Achievement During the Early Stages of Learning a Musical Instrument,” Council for Research in Music Education 147 (2001), 122-27 2. “The Talent Code-Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s grown. Here’s How” Daniel Coyle, (New York: Bantam Dell, 2009), 104-105 3. “Developing Talent in Young People,” Benjamin Bloom, (New York: Ballantine, 1985) 173-76 4. “Rousing Minds to Life: Teaching, Learning, and Schooling in a Social Context,” Ron Gallimore, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988) 5. “Make It Stick- The Science of Successful Learning,” P. Brown, H.L. Roediger III, M. A. McDaniel, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 90-91 6. Ibid, 92

1 Comment

|

AuthorLook for Mindful Music Academy Facebook page. Archives

March 2020

Categories

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed