|

I made these videos a while ago for the Iowa Music Teacher Association, following their curriculum. More videos that were interactive (with quiz questions and multiple choice answers) were hosted on TechSmith (Camtasia) but are now defunct as I now live in California. Levels are A to F on the YouTube channel. Answers are in a google document that can be shared if you email DoLearnMusic@gmail.com How teachers nurture themselves is how they can nurture their students. Research suggests that a teacher’s stress level is affecting students’ physiological stress regulation.(1) In order to be at our top game for each youth, let’s be mindful of how our well-being is affecting our student’s stress levels. In some ways, our passion for music is their passion for music, our joy during a lesson is their joy, and so our stress level can affect their stress level as well.

There are only twenty-four hours in a day. Six to eight hours of that time should be spent in sleep. The brain and its creative juice depend on the type of sleep that we get.(2) Research also suggests that “Aha” moments are more likely to appear during rest periods.(3) So, for a teacher to be creative, sensitive and responsive to the immediate needs of a student, a teacher needs intentional breaks in order to bring “play” back into playing an instrument. The power of “play” in developmental psychology is a well-researched area in early childhood education,(4) but perhaps “play” can also be part of adults’ wellness programs. How can adults re-learn how to “play”? Through Mindful Play. Mindfulness is to pay attention to the present moment without judgment. Easier said than done. Not only is Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) now an internationally-known evidence-based method, covered under certain healthcare plans, there is research suggesting that mindfulness meditation can lead to activation of specific brain regions associated with regulatory systems such as attention and emotions.(5) How can we see Mindful Play in action? Observe children. When I teach four and five year olds, I am in awe of their fearlessness, their spontaneity, and their joyful curiosity. Anything and everything could become a game, a toy, or an object of interest. In other words, they really know how to play. Once, I used a hand puppet to talk to a four years old student. As soon as the puppet came out, the child exclaimed: “I can see your hand in there!” But then when the cute puppet clapped, cheered and begged to hear the song “three more times, one for each ear!”, the child played along, and in this role playing, the twinkle in his eyes says it all. In that particular moment in time, he believed it was real, he was totally focused, and he conversed back, responding that we only have two ears. He would not do repeats for me, but he would do them for that puppet! My student was navigating uncertainty with confidence, trust and joy. He knew the puppet was not real, he knew he was being manipulated to do more repeats, but the connection to that puppet was so real that he allowed himself to joyfully believe in it. Adults could practice this, bringing “play” back into our lives, intentionally reconnecting ourselves to simple things that bring us joy, and allowing the child that is in all of us to come out. To be mindful is to connect to what is “real.” This very minute is the moment that is most “real.” Let’s experiment. Look somewhere else than these lines while sitting in a comfortable upright posture, and take a few breaths. Did you notice whether the left nostril was inhaling more than the right one? If not, try breathing again! Did you notice whether the weight distribution between your left and right butt cheeks were equal? Or did you hear a sound you did not hear before? There are many things we do not notice during a day, and the simple act of focusing on a few breaths can bring a lot of joyful little breaks into our day. Having a chance to just be. A side effect of a few breaths is that most people feel grateful for the things they took for granted: the fact that there is no toothache that day, the realization that the ears can hear sounds and the eyes, see colors, the miracle of a heart still beating. For most of us, after a few breaths, thoughts will start to wander, into the past, or the future, planning, reviewing, analyzing... When that happens and we notice it, just gently bring the attention back to the next breath, without self-criticism. Mindful breathing is not about a perfect way to breath, it is about how we relate to the experience of breathing, the instinctive reaction we have to our wandering mind. For novice at meditation, thinking may happen a dozen times in a five-minute breathing session, and that is perfectly normal. Bringing awareness back to the breath again and again, without judgment, is part of the practice. Many teachers don’t have time to do half an hour of meditation daily, but a few breaths here and there can still be nurturing. A mother with young children has told me that before she gets out of her car to go inside her home after work, she sits there quietly for a few minutes, enjoying the peaceful cocoon of the car. She takes a few deep breaths, bringing attention to her body sensations, taking inventory of thoughts and emotions that had come and gone that day, and only then she steps out of her car, feeling refreshed. To supplement the longer but rare periods of meditation, I try to find spurts of time to regain energy while doing mundane tasks: waiting in line, driving, cooking, eating, or washing dishes. The quality of attention one can bring to fully live the present moment while doing boring but necessary tasks can transform these tasks into spurts of joy and appreciation that can lower stress level and give perspective to a chaotic life. Washing dishes at the meditation retreat center was pure unadulterated joy. Having nowhere to go, nothing really important to do, no other dishes to wash but my own, and washing with a totally focused mind on the task at hand, was surprisingly pleasurable! Standing there in the warm sunlight, hearing birds and the rustling of the leaves, feeling the fresh water caressing my hands, giggling at the sight of bubbles popping on the surface of the soapy water, feeling the urge of playing with the water like a toddler in a bathtub… Somehow, washing dishes was a heaven on earth! Once experienced, never forgotten. Students should be told that the first note produced on an instrument on any given day is a miracle, and that they should feel as if from deafness they can hear for the first time, then that first note will be produced with care. If they had practiced feeling little miracles in ordinary tasks, such as taking care of a single step (mindful walking), being aware whenever and wherever they sit (mindful sitting), or taking time to chew a single bite (mindful eating), it would be easier to treat that first note as a miracle To reignite the spark of a beginner in daily life (Mindfulness) is to remind ourselves to rediscover sound and to rediscover joy as if we were four years old, once again. Life is filled with uncertainties, except for death, and so if we re-learn how to trust, to re-frame the bumps we meet on the road, small little miracles will reveal themselves to us, and life will be a little more joyful. References:

Read these two columns

A B milk/juice br_ad / b_tt_r chair/table sh_e / so_k ocean/whale r_v_r / f_sh Now without looking, try to remember as many pairs of words as you can. From which column did you recall more words? Did you have more difficulty reading column B? If you are like most people, you will remember more from column B. Studies show you’ll remember three times as many. “Deep Practice” is a term Daniel Coyle used in his book, The Talent Code. “Deep Practice is built on a paradox: struggling in certain targeted ways - operating at the edge of your ability where you make mistakes- makes you more efficient.” 1 In the previous example, the mere fact of making an effort to read is enough to mark a larger imprint on our memory. “We think of effortless performance as desirable, but it’s really a terrible way to learn, said Robert Bjork,” 2 the chair of the psychology department at U.C.L.A. Students will learn best when they are forced to make an effort, when they allow themselves to make mistakes. This attitude is crucial for a learner‘s resilience. Learners’ tendencies to persist in the face of difficulty are strongly affected by whether they are “performance oriented” (fixed mindset) or “learning oriented” (growth mindset).3 When a mistake becomes an opportunity for learning and problem solving, students will strive to do better every time because they believe their learning capability can grow. Hence, how many retakes of an exam should a teacher give? Or after a teacher asks a question, how many seconds should he or she wait before giving out the answer? Cognitive science research seems to indicate that giving students the chance to make a mistake in a low stake situation is a more effective way to help them learn. They will remember much more as well as gain problem solving skills. They will also learn to overcome mistakes, learn about the way their memory works, and develop a growth mindset. Most music teachers would agree that after a certain minimum level of required practice, it is not the amount of time one spends in music practice that matters, it is the way one practices. Yet there is a limit for how much “deep practice” human beings can do in a day. Ericsson’s research shows that “most world-class experts-including pianists, chess players, novelists, and athletes- practice between three and five hours a day, no matter what skill they pursue.”4 This is probably because “deep practice” would have drained our brain power, and we would not be able to concentrate after three hours. If we were truly in “deep practice” we should also have the impression of continuing to rehearse the material we just learned while we rest. Students have told me that they dream about their music pieces after intense rehearsal sessions. Research suggests that when rehearsals are spaced out, the brain uses that rest period to consolidate that new information or skill and transfer it into long term memory.5 When studying alone, it is hard to push oneself out of our comfort zone to get into this “deep practice” zone. When we repeat or re-read without a clear goal, we tend to zone out and let automaticity take over. This happens to some of us when we drive and take a wrong turn because that is a turn we often took. Sometimes it takes an outside source, a teacher, a peer, or even an object, such as a random alarm, to help us realize that we were zoning out. David Kahneman, in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, cited an experiment which proved that the initial “effort” we make, even unconsciously, can make our mind jump to a higher level of engagement of the brain. In one experiment, the same test questions were either badly printed or well printed.6 This simple visual difference resulted in a wide variance in students’ scores. Students faced with the badly printed questions were better at answering tricky questions than the ones who had an easier time deciphering the exact same questions! Why? The initial effort made to read the badly printed words engaged their brains, and prepared them to think harder. Experiments in skill development find that humans tend to plateau after a certain point. One example of this is in speed typing. In the 1960s, psychologists Paul Fitts and Michael Posner described three stages anyone goes through in acquiring a new skill. The first stage called the “cognitive stage” is when one intellectualizes the task and finds strategies to accomplish things more efficiently. 7 The second stage, the “associative stage,” is when one is comfortable enough and spends much less energy concentrating and making fewer major errors. The third stage, called the “autonomous stage,” is when one plateaus and most skills learned are now running on automatic pilot. In fact, the latest research on neuron myelin building suggests that we are built to automatize skills as soon as we can. “The more we develop a skill circuit [in our neurons], the less we’re aware that we’re using it.”8 As soon as a particular skill is getting easier, another part of the brain, the cerebellum, is taking over this more or less automatized task, and we have more brain power to devote to other tasks. In fact, the latest research on neuron myelin building suggests that we humans are built to automatize skills as soon as we can. “The more we develop a skill circuit [in our neurons], the less we’re aware that we’re using it.”8 When one can be on automatic pilot Csikszentmihalyi calls it the feeling of effortlessness, flow, or “in the zone”. Flow theory is now a common word in positive psychology. But Deep Practice is to prevent us from getting to that automatic stage. It is more like a laser-sharp pointed mind, like sitting on the edge of a fence, where balance is crucial. In order to prevent this automaticity and remain in the “deep practice” zone, teachers will have to come up with many ways to engage their students at the right level, scaffolding on what they already know. Since Deep Practice is a way to develop more efficient learning, and it can be practiced, it follows that continuous Deep Practice will build a growth mindset. Students with fixed mindset will tend to take feedback very personally, they avoid failures and challenges because they want to perform well, so they stick to what they know. Students with a growth mindset will “go out on a limb because that’s where the fruit is”, 9 they embrace challenges, they are not afraid to make a mistake because they know these are opportunities to learn; they take constructive feedback as an assessment of their current state, and they believe they can learn to do better. In order to build self-efficacy and life long learners, teachers should encourage growth mindsets and give students opportunities to reflect on how they learn, to understand how mistakes occur, and guide them to find solutions.

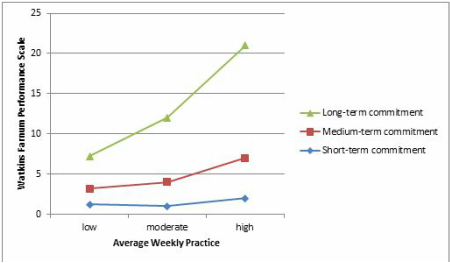

It’s all in the idea: Student self-perception and musical success

In 1997, a group of children (seven or eight years old) was studied from the time they choose their instrument to their graduation in high school. The researcher wanted to know what factors predicted their musical success or failure. Was it a sense of rhythm? More aural sensitivity or motor control? Their family’s income level? or their IQ? None of these factors were predicting the musical skill level of a student. Instead, it was their answer to a question that was asked before they had even started their first lesson: “How long do you think you’ll play your new instrument?” Those who answered longer periods were labelled “long-term commitment” in the top graph.1 When predicting musical performance level, the children’s initial commitment and their self-perceptions seem to matter more than their amount of weekly practice. This fact can be seen in the study’s graph at the top. For students who practice a lot, those without much commitment or self-perception as a musician will ultimately end up with a lower level than those who committed from the beginning and could envisioned himself or herself as a potential musician.2 Perhaps a teacher needs to nurture this vision of an ideal future musician as much as teaching motor skills, aural skills and intellectual skills. How does a teacher nurture the visions or self-perceptions of these potential musicians? One way to ignite that fire within is to expose them to a role model. In the field of sports, films and business, the media exposes all of us to role models to inspire us to reach for the stars. Unfortunately in the musical field, those role models are not as readily available. Whenever possible, be a role model, play for your student. Encourage them to go to live concerts, master classes, or to listen to more advanced students. Another way to nurture the vision of a future musician is to teach them with love. In the 1980s Dr. Benjamin Bloom surveyed one hundred and twenty world class pianists, swimmers, mathematicians, neurologists, sculptors and tennis champions. The majority of these experts rated their first teachers as “average.” These virtuoso pianists stayed with their first teacher for five or six years. The majority of the descriptions they gave for their first piano teachers were about how kind, nice, likable and patient their first teachers were. “The effect of this first phase of learning seemed to be to get the learner involved, captivated, hooked, and to get the learner to need and want more information and expertise.”3 Another facet of this nurturing process involves guiding students positively through unsuccessful attempts. “Great teachers see and recognize the inarticulate stumbling, fumbling effort of the student who’s reaching toward mastery, and then connect them with a targeted message.”4 A fear of failure can make students avoid experimentation and risk taking. Yet failure is at the core of the scientific method: without failed experiments one can’t eliminate hypothesis in the search for truth. Likewise, in music, mistakes are necessary for self-discovery, skill mastery, and good performance under pressure. Some teachers never force a timid student to play in front of others. Yet all failures can be turned into opportunities for learning. If a student believes that errors are just part of the learning process, he or she will recover from a performance with mistakes. Some teachers believe that they should write out all fingering for students. These teachers may believe that if learners make errors, the errors will be reinforced. In music learning this is especially true because “muscle memory” makes changing fingering hard once fingering is learned. In order to avoid “wrong” muscle memory when tackling a technically more challenging piece, teachers should spend time letting students choose fingering and then immediately give feedback. For intermediate students, a teacher can explain the phrases requiring lifts, range of keys within a phrase, black keys versus white ones, or structure of hand and fingers. For more advanced students, a teacher can explain why certain fingering works best for their particular physical attribute and what works best for that particular piece. Other topics related to fingering choices include what sound quality one aims for, which tempo, dynamic or articulation one wants, whether the reflexes or weight of our wrist, forearm or whole arm should be considered, or whether the previous and following beats or measures should be considered. I had the grace to have met a teacher who exclaimed, every time I made an unexpected mistake: “Wonderful! You’ve just stumbled where you normally do not. Let’s figure out what happened so you will secure it for future performances. Now where was it exactly?” Finding the location was a puzzle to be solved, after which we figured out “together” what was in the previous beat or motion, and what type of sound I should aim for. I was lucky enough to be taught by a teacher who believed that everyone can learn music, and who let me stumble, even in public. I learned how to pick up the pieces and continue, during a performance as well as after one. When making a mistake becomes an opportunity for learning, a student will tend to persist.5 Research suggests that kids who are praised for their efforts will more likely take on more challenges than those who are praised for their innate talent, or their successful results. It is all in the idea of learning: an error is not a measure of ability, effort changes the brain,6 and anyone can become a musician. A child has the opportunity to believe that he or she can be a musician. Our job as teachers is to nurture that vision by providing a positive nurturing environment. Notes: 1. “Commitment and Practice: Key Ingredients for Achievement During the Early Stages of Learning a Musical Instrument,” Council for Research in Music Education 147 (2001), 122-27 2. “The Talent Code-Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s grown. Here’s How” Daniel Coyle, (New York: Bantam Dell, 2009), 104-105 3. “Developing Talent in Young People,” Benjamin Bloom, (New York: Ballantine, 1985) 173-76 4. “Rousing Minds to Life: Teaching, Learning, and Schooling in a Social Context,” Ron Gallimore, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988) 5. “Make It Stick- The Science of Successful Learning,” P. Brown, H.L. Roediger III, M. A. McDaniel, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 90-91 6. Ibid, 92 “In the Beginning was the Word, and the word was what made the difference between form and formlessness” (Ali Smith)

Once a word is spoken, its power is out of our hands. Once an idea is defined by a word, it is humanized, limited, as we are. Take the word God. Many centuries ago, one could not name or casually write Yod Hei Vav Hei (YHVH). Why name something that is beyond all names with one single word? How can one word represent all that humans can barely grasp? Sonata and Symphony are musical forms that restrained creativity. During two centuries they were extended and transformed by great composers who developed musical language, pushing boundaries. Nowadays those words are insufficient; composers invent their own forms to express ideas. Some still pay tribute to tradition, but outside of their social context, those words, Sonata and Symphony, have exhausted their potential meanings. Sometimes words seem to point to the same idea, but on a closer look, they imply more than their definitions in a dictionary. Take another common word, “happy.” In the current English speaking world, partly thanks to Bob Marley and Pharrell Williams, the word “happy” has come to exude more of its exciting aura, as in “being joyful, delighted or blissful” than reflecting its more subdued connotations, as in “being pleased, satisfied, or glad.” For the French, the word “heureux” has retained its contemplative flavor, more often associated with Content (contented), Bonheur (happiness), or Comblé (Filled). In Vietnamese, the word “Hạnh Phúc” consists of two words, both of Chinese origin. Hạnh means “beloved, lucky, or blessed.” It connotes something precious one receives from outside as in befalling luck. Phúc is a word that can be understood only through the beliefs and customs regarding karma and veneration of ancestors, both well established in Vietnamese and Chinese cultures. Phúc is the immaterial goodness one leaves behind for future generations. By extension, it is our ancestors’ heritage. “Hạnh Phúc” suggests a communal society for whom ancestry is valued. It is Confucius’ legacy. Perhaps the extroverted “happy” insinuates the value of an extrovert American society where assertiveness and self-confidence are valued over other virtues. Thus in learning a new language, a new word, one also learns its construct, its implication, and the culture it represents. What about learning the musical language? When teaching a beginner, should one limit the definition of “p” as “soft” and “f” as “loud”?, or “p” as “as loud as the lullaby a mother sings,” or “the natural sound from the weight of one’s bow or arm,” and “f” as “the amplified sound one projects when talking in a Roman amphitheater,” or “when our whole body participates,” or “when a warm breath is blowing evenly as the wind blows through a leafless tree?” As “p” is now used in books estranged from its original context of the Renaissance where dynamic markings were inconsistent, why should we assume that one definition is enough to communicate articulation, mood, sound texture, temperature, attack or decay? Moreover, many musicians have their own “p” sound for particular stylistic period and adapt this “p” not only to the composer, the particular work, but as well, to the acoustics of the performance space and the audience. In separating a sound into its components, as most introductory method books do, one loses qualities not so valued by a specialized society: imprecision, ambiguity, adaptability, hence, creativity. Dynamic, tempo, or pacing signs are elements that make music, and they are interrelated. It may be useful to break them down into components, but dangerous to teach each element as separate entity from all that makes music, for music is a much larger encompassing word. It is bigger than the sum of its parts. When learning a new song, should a beginner learn only the pitches first and then the rhythm? How often should a student repeat the whole song with focus on getting only the pitches correctly? Would it be better to incorporate rhythm and pitches, but only play one short phrase at a time? For the more advanced players who can read both rhythm and pitches, should correct fingering and technique to express the articulation or dynamic be the simultaneous goals of one short phrase, or should one just play through the page to get a sense of how it goes, and add dynamic and articulation later when the page is in tempo? When these words, tempo, articulation, dynamic, were invented, they were signs for a whole meaningful experience with sound. “In the Beginning was the word,” and the word became sound. That is how we should be initiated to music. Like a baby recognizing a mother’s voice after being introduced to air, so shall we be recognizing sound before seeing its representation, or hearing its definition. I have encountered beginner adults who have not learned how to read notes. Many learned through youtubes, websites, and some have only taken a one credit class in music theory, from the very basic staff to the major scale. Many have great ears. One of my students picked up "Girl with the flaxen hair" Debussy prelude by ear.

When oral tradition was replaced by written ones, from orators to scribe, the written words themselves (in Greek) had no space. Written texts were used to remind ourselves what we already know. Learners already heard the speech many times and the written words were just a little help along the main thread, the core idea. Music notation started in the same way, from imprecise neumes to overly prescribed articulation, dynamic and pacing symbols. As men controlled more and more of his/her environment, the world specialized in all field, including music. Interpreters were separated from composers. We began to rely on our sight before hearing the sound. Charles Hicks in the 1980s published in the Music Educator's Journal "Sound before Sight, strategies for teaching music reading." The advice is logical, with emphasis on continuity, repetition, repeated patterns, narrow range, same key signature, generally a constructivist approach (always add one new element with something familiar). his recommendation was that the PRINCIPLES of notation rather than the SYSTEM of notation should be explored. In what ways can this translate into a lesson plan? Hidden in the writing of symbols are organized SOUND. If one can help a student first notice how sound perception can be organized and classified: in time (double the speed?), in pitch (higher or much higher?), in volume, in attack (choppy or smooth?) or lines (where are the sentences?) before one introduces them to the written notation, it would help contextualize the purpose of learning these new symbols. When we learned to speak we learned by imitation. Why should one learn written music before one learns what a regular beat is, and what one can do with that duration in time? With very young children I have many rhythm games, or solfege games, based on what I learned at Suzuki camps, or with pedagogue such as Michiko. For pitch changes, aside games that required physical big motion such as walking on a staff, or arm motions for steps or skips, I also devised a mnemonic system of drawings. I doodle these images on a blank page without staff. After a while it is a matter of drawing a symbol of the animal in question to the notes on the staff, and gradually erase those drawings after explanation of the motions on the staff. Chords were color coded, tense chords were red or orange (dominant or sub-dominant) and the "home" chord was green (tonic). Children can learn the broad brushstroke before the exact note, or even their names. About 16 years ago I met an adult at a community college who was a wonderful intermediate pianist in a chamber ensemble. She could not name any single note. She could not find the third beat of measure 33. She could, on the other hand, start anywhere if I point to the exact spot on the page. I thus learned not to give out anymore written games of naming notes without sound or keys to press. My very first questions to adult beginners are usually about their goals in taking piano lessons. Some would like to reproduce songs or pieces, some like to create, some, to accompany themselves singing, others say they have the treble clef down but would like to learn the bass clef, some "doodle" on the keys. My second question is usually about what kind of songs or pieces they listen to, in order to know what to use to motivate them, or ask them to show me what they "doodle". The third step is trying out how fast they can learn by imitation, and gage how much exercise to give for coordination and small motor control in warm ups. Adults can handle reading notes from the very first lesson, but many are stuck with the trees (naming of each note) and have difficulty seeing the forest (motion of notes or shapes of chords). Our music education system puts a lot of weight on the Oral, less on the Aural tradition; it is leaned toward the visual rather than the audio part of learning music. Folk or Art music around the world are, for the most part, still transmitted by oral tradition. Even when written down, they require close encounter with an instructor, because learning is through exposure, enculturation and imitation. In India, a novice just listens for a year before attempting to improvise lightly a scale (raga). Years can pass before he or she is allowed to imitate licks of the teacher. Here in the U.S., there are students technically proficient who barely go to one concert a year. With certain other instrument, such as trumpet, hearing the sound is extremely important as the same buttons may be pressed, but the way one blows determines the pitch. In order to know whether or not one has blown the right pitch, one has to hear it first. Why don't we learn piano the same way? Less like a typewriter, more like a musical instrument. How many of us teachers have encountered a student that played Ode to Joy with the dotted quarter note - eighth note instead of the written quarter notes? They are guided by what they hear on the inside. Most beginner piano books start with what they consider standard repertoire that everyone should know, such as Mary had a little lamb, Jingle bell and so forth. Please don't change the rhythm! This repertoire is also not updated nor culturally relevant. The Mexican Hat is not what Mexican Americans listened to, and most of us know "Oh When the Saints" (except new immigrants which I have taught) but some of us also know Amazing Grace, or the latest Lady Gaga, Birdy or Pentatonix. If the point is to teach something familiar, then we need an online continuously updated book for the younger generation. One where they can go in and choose songs they know, arranged for different levels, and print out song by song as they progress and taste changes. As for the different types of arrangements one can do for each song with a chord chart, this can be learned in workshops, webinars, or conferences. I hope more publishers will go back to our tradition of putting Sound before Sight.

The Iowa Music Teacher Association (imta) under the umbrella organization "Music Teacher National Association" (MTNA) hold auditions each year for pre-college students. As chair of the Theory committee I have made a dozen interactive videos (according to the guidelines of the state) as free supplementary materials for local teachers and their students. Under the videos tab you can find samples of those videos.

Click to set custom HTML

It is never too late to learn. Brain cells may die, but new pathways can always form. As our mind compartmentalize in order to make sense of the world, the brain is still the most flexible organ a human possess. Called Plasticity, it should give musicians and want-to-be musicians hope to be renewed. Dr. Charles Limb pictured above (Limb, 2008), of the JHU Medical School, has spent more than ten years studying the brain activity of musicians as they improvise. Using MRI machines, he has found that the region of the brain associated with decision-making and self-censoring (the prefrontal cortex) is slowed down when one improvises. Hence, when one improvises, inhibitions are lowered and cognitive blocks are reduced. As a classical musician, have you had thoughts during performance, hindering your full potential? What do you think, how do you feel, and what do you do when you make a “mistake” during a performance? How aware are you of your balance between “control” and “letting go” during a performance? When one improvises, there can be no mistake, just choices and consequences. Even in Classical music, there may be numerous options to shape one particular phrase, so options of sounds, articulation, pacing and so forth will be depending on the first few notes. To embrace a mistake is a difficult attitude for musicians to adopt, as the digital age convinced the world that there is such a thing as a perfect performance. The model of competitions where one sensitivity is pitched against another for judging, is the wrong model to produce true musicians who enjoy playing music without self-criticism turned on permanently. Perhaps improvising is one way to regain our freedom. The freedom to be expressive, the freedom to make "mistakes" and still make music. Try it if you haven't. |

AuthorLook for Mindful Music Academy Facebook page. Archives

March 2020

Categories

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed